By Dražen Huterer, Edib Bajrović, Mladen Lakić

The emerald-green River Neretva runs through Mostar, a beautiful city in southern Bosnia. It is a popular tourist destination, but also a symbol of the country’s enduring divisions.

The 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement which ended the war also divided the country into two administrative entities – the Bosniak- and Croat-majority Federation and the predominantly Serb Republika Srpska, RS.

All of Mostar is in the Federation so unlike some other towns, it is not divided by the boundary that divides the two entities. Nevertheless, it is still suffering from the rupture it underwent in the war of 1992-95.

Prior to the conflict, around 35 per cent of people in the city were Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), 34 per cent Croats and 19 per cent Serbs. When fighting broke out, Bosniaks and Croats allied against Serb forces, and most of the Serb residents fled the city.

Then, in January 1993, a conflict erupted between Bosniaks and Croats, and Mostar was divided into the Croat-dominated west and the mainly Bosniak eastern part, a situation which still persists.

Today, Mostar remains deeply divided. The city government barely functions because the Bosniak and Croat representatives can rarely agree on any important issue.

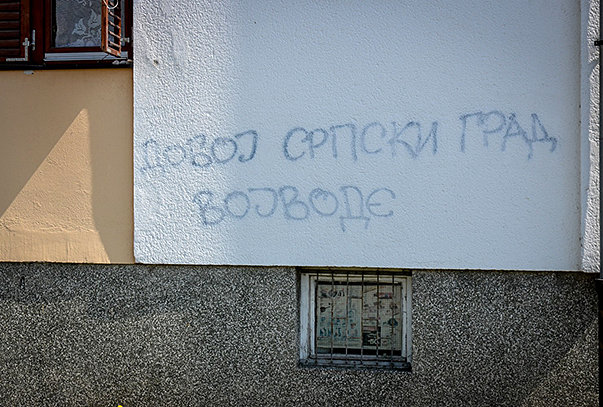

The 8,000 Serbs who remain in Mostar – down from a pre-war figure of 25,000 to 30,000 – say they have very few rights, especially because of the constant power struggle between Bosniaks and Croats, who pay little attention to their needs.

Most of the Serbs who fled Mostar in 1992 currently live in the nearby towns of Nevesinje, Gacko and other locations inside RS.

Ratko Pejanovic commanded a firefighting unit before and during the war. Now he is vice-chairman of the Serbian Civic Council and a human rights activist.

Sitting in a Mostar cafe on a hot summer afternoon, Pejanovic sets out some of the problems created by the boundary between the Federation and the RS.

“The administrative division is a problem,” he noted. “Someone from Nevesinje in RS, only 35 kilometres from Mostar, cannot be treated in a Mostar hospital because their health insurance is only valid in RS. So they have to travel all the way to Banja Luka, some 250 km away, or else to some other centre in RS with adequate medical facilities. That’s absurd.”

Milan Jovicic, former chairman of the Municipal Council of Mostar, agreed.

“Why can’t those living in Nevesinje, Gacko and other towns and villages close to Mostar use health services or go to high schools or universities in this city, instead of going to Banja Luka which is so far away? That’s nonsense. It’s sad and tragic,” said Jovicic, who still lives in Mostar.

Zoran Laketa, a Serb from Mostar who dislikes being labeled as part of any ethnic group, was 25 at the outbreak of hostilities in 1992.

His father was conscripted into the Yugoslav People’s Army. When Bosniaks and Croats turned against each other in Mostar, Laketa fled to the Croat-controlled west of the city, while his brother and mother remained in their house on the east side. Laketa joined the armed forces of the Croatian Defence Council, while his brother was enlisted in the Bosnian government army and was killed during the war.

“It’s hard to live with the fact that my brother and I shot at each other back then, and that the war divided us in such a weird way,” Laketa said.

He finds it hard to accept that Mostar remains divided so many years after the fighting stopped.

“Before the war, I used to be proud to say I was from Mostar,” he said. “But now I’m ashamed to be part of this absurd division. Whenever I go somewhere and tell people where I live, they immediately ask me if I am from east or west Mostar. I don’t like that at all, but that’s the reality we live in.”

TRNOVO: THINGS WORK DESPITE DIVIDE

The line dividing Bosnia’s two administrative entities runs right through Trnovo, a picturesque small town some 30 km south of Sarajevo.

Before the war, 66 per cent of its population were Bosniaks and 32 per cent Serb. When fighting began between Bosnian Serb forces and the Bosnian government army, most of the town’s people fled the town, and began returning only after the war.

Today, part of the town is in the Federation, another part is in the RS, and two thirds of the Trnovo municipality lie within the Federation.

Despite the fact that both town and municipality are divided, Trnovo residents claim that there are no ethnic tensions and that they live in harmony.

“This place should serve as an example of coexistence in Bosnia,” said Meho Pozder, a local Bosniak man. “We used to celebrate everything together before the war – religious holidays, birthdays, weddings… It didn’t matter to us whether someone was Serb or Bosniak. But then the war broke out and most of us fled,” Pozder added.

During the war, Pozder was in the Bosnian government army, fighting neighbours who had joined the Bosnia Serb military. But he insists that this history has not affected relations between him and local Serbs.

“We’ve left all that behind,” he said. “We realised the war was stupid and we went on with our lives, living the way we did before the war. We still celebrate joyous events together, and share our problems.”

Yet while relations may be cordial on a personal level, the administrative dividing line can make life very difficult.

After the war, Pozder returned to Trnovo to rebuild his house, which had been damaged in the fighting. He asked officials at Trnovo’s municipality for assistance, but had to deal with multiple hurdles.

“I took all the required documents to the [Bosniak] mayor of the [Federation] municipality of Trnovo, but he refused to help me because according to the entity line drawn at Dayton, my house was in RS,” he said. “I then walked 100 metres to the [RS] Trnovo municipality where the [Serb] mayor told me that although my house was indeed in RS territory, my ID card had been issued in that part of Trnovo belonging to the Federation, so I was not entitled to the payment intended for RS citizens.”

He added, “These are idiocies that a normal person can’t even comprehend.”

Goran Golijanin, director of the Trnovo Cultural Centre in the RS sector, agrees that despite the administrative division, people in the two parts of Trnovo get on well.

“When we run programmes for children, we always get in teams from the Federation part of Trnovo as well,” he said. “No one has ever mentioned divisions, and we’ve never had any incidents.”

Golijanin said it was politicians who created divides, and there were some towns that simply rejected them.

“Despite the fact that we all suffered in the war, that most of us were driven out, and that we still barely make ends meet, we are smart enough to know that the divisions are imposed on us by political leaderships on both sides who are promoting their own interests,” he said. “I believe that 95 per cent of people think the same way I do, so there are no real divisions among us.”

DOBOJ: DIVIDE APPARENT ON THE GROUND

Located in the north of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the town of Doboj was – before the war – the municipal centre of an area of some 690 square kilometres with more than 100,000 inhabitants. In 1991, 40 per cent of Doboj’s population were Bosniaks, 39 per cent were Serbs and 13 per cent Croats.

Under the Dayton agreement, the municipal area was divided into the Doboj town in RS, and Doboj East, Doboj South and the Usora municipality, all in the Federation.

Bojana Lugonjic, a journalist who lives in the Doboj, says life in the area is not easy.

“There is no work,” she said. “Young people cannot expect a better future, and the situation is further complicated by the ethnic and religious divisions which affect all aspects of life.”

Lugonjic pointed out that the town has two cultural centres – one Serb and one Bosnian, attended mostly by Bosniaks.

“All the activities at the Serb centre are tailored to suit Serbs only, while those held at the Bosnian centre are mostly attended by Bosniaks,” she said.

Lugonjic recently attended an event organised by local residents to raise funds for medical treatment for a young Bosniak man who was seriously ill.

“Even in this case, each cultural centre organised its own fundraising. That speaks volumes about the way people here live and how they think,” she said.

Elmedin Skredo, a Bosniak who lives in Doboj East in the Federation, says that ethnic animosities are a problem across the whole country, not just in Doboj.

“Having the sort of division we have in Doboj is weird, but we can blame our politicians for that,” he said.

Skredo works for the International Solidarity Forum, EMMAUS, and he is often involved in projects bringing together people of different religious and ethnic backgrounds.

“Immediately after the war, [Bosniak] people would have problems if they went to Doboj town; there was a lot of tension there. But I don’t see that today,” he said, adding that what gives him hope is that ordinary people are becoming increasingly aware of the absurdity of such divisions.

Mensud Halilovic, a Bosniak who lives in Doboj town, part of RS, but works at a school in Doboj South in the Federation, says the people he knows are much more concerned about the country’s economic future than ethnic divisions.

“You can see that life is getting harder,” Halilovic added. “No one knows how long they will have jobs, and that’s the biggest problem for us, not our religious or ethnic affiliation.”

Snezana Seslija, director of ToPeeR, a Doboj-based NGO that works to promote coexistence, says local people are tired of divisions and the problems they cause.

When it comes to the future, Seslija is an optimist.

“We all lived together before and, of course we’ll continue doing so,” she said.

This article was produced as part of Tales of Transition project funded by the Norwegian Embassy in Sarajevo. SCCA/pro.ba is carrying out this project in co-operation with the IWPR and EFM Student Radio.